By Harleen Gambhir

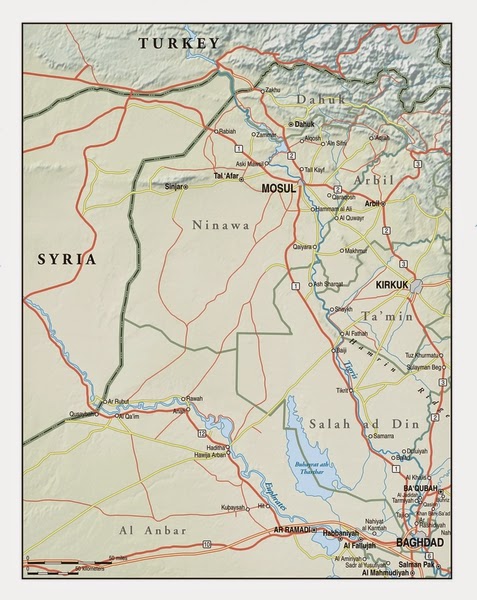

Key Takeaway: The current Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) offensive in Baiji presents a critical opportunity for the ISF to open a gap in ISIS territory, and to set conditions for a future movement towards Mosul. Baiji is an operational node and likely proximate to an ISIS command and control center; its loss threatens a central corridor of the ISIS caliphate, and could facilitate isolation between ISIS’s military areas of operation within Iraq. In response to ISF pressure, ISIS has moved to reinvigorate control over Tikrit and Alam, east of Tikrit. If the ISF gain control of Baiji city and the Baiji-Haditha road, ISIS will likely move to secure supply lines to Syria in northwestern Iraq, and refocus on closing gaps on its Anbar front.

For the ISF

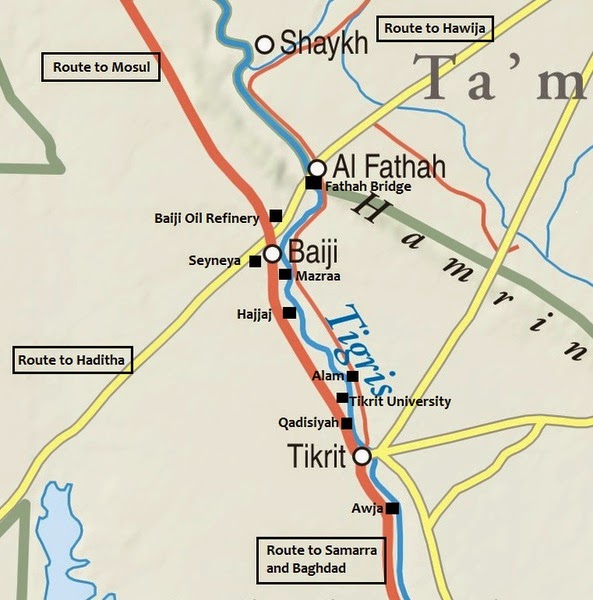

ISIS captured Baiji city on June 12, moving south from Mosul in its swift urban offensive. Since then, ISIS has both held Baiji city, and controlled the key Iraqi highway stretching south from Mosul to Tikrit. Denied access to this route, the ISF have been compelled to reinforce the ISF-held Baiji Oil Refinery, northwest of Baiji city, by air.

Though Iraqi Aviation launched airstrikes into Baiji multiple times over the past four months, no ground offensive was attempted until the ISF’s current effort. During the same time span, ISIS repeatedly initiated complex arms attack on the refinery, in order to control lucrative oil infrastructure and to close a gap behind the ISIS line from Mosul to Tikrit. As of November 3, the date of the most recent attempt, ISIS has not been able to control the refinery.

Through its current offensive, begun on October 24, the ISF aims to gain freedom of movement on the critical stretch of road from Tikrit to Baiji, and to take control of Baiji city itself. If successful, the operation will mark the first time that the ISF has retaken a major urban center from ISIS since the terrorist group’s June 2014 offensive. Control of Baiji city will also give the ISF a launching point to re-establish a ground supply route northwest of the city to the Baiji refinery. This route will allow the Iraqi Government to resume use of the oil facility, and establish a line of communication between two previously isolated ISF-held areas, Tikrit University and the Baiji refinery.

The loss of full control of Baiji is a significant blow to ISIS, and presents a key opportunity for the ISF. Baiji is a strategic crossroads that connects ISIS routes across the border to Syria, southwest to Anbar, south to Baghdad, and east to the Hamrin Ridge. Its environs are thus a likely area for ISIS strategic command and control. Since ISIS’s June 2014 offensive, the ISIS military stronghold in the historic Za’ab Triangle has provided forward protection to the ISIS political stronghold in Mosul. Equally as important, the Mosul-Tikrit highway has served as a central spine of the caliphate, from which ISIS has projected force to Mosul, Hawija, and Tikrit. The ISF and Shi’a militias have thus taken advantage of a critical ISIS vulnerability: peripheral control zones that, when opened, allow the ISF within striking distance of ISIS’s interior strongholds.

ISF’s Baiji offensive has opened a gap on the Mosul-Tikrit line, at the same time that ISIS efforts to close gaps on the Anbar front have stalled. It is possible that ISIS miscalculated its defensive requirements in central Iraq, committing forces to active fronts and leaving its core undermanned. As a result, ISIS may be facing the loss of key lines of communication among its Iraq efforts. The Baghdad Operations Command regained control of the Samarra-Ramadi road on October 28; the further loss of the Baiji-Haditha road would force ISIS to travel through Syria and down the Euphrates corridor in order to communicate and supply across the central Iraq and Anbar systems. This task will be increasingly difficult, as U.S. and coalition forces follow through on a stated intention to separate ISIS’s Iraq and Syria forces.

The ISF push for Baiji began with movement from north of Tikrit, led by the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Services (CTS). From October 24 to October 27, the ISF’s Golden Division cleared the Hajjaj village, north of Tikrit. U.S. and coalition partners provided air support throughout the operation. At the start of the ISF’s activities in Hajjaj, on October 24, five coalition strikes targeted an ISIS training camp and ISIS vehicle south of Baij city. Iraqi news sources reported that the strikes killed militants who were planting IEDs in the Mazraa area, north of Hajjaj on the road to Baiji.

After clearing Hajjaj on October 27, the Golden Division moved north, reportedly slowed by roadside IEDs. U.S. aircraft accompanied this movement, targeting ISIS north of the city, south of the Baiji Refinery. On October 30, ISF took control of Mazraa and the Sinai area southwest of Baiji. The same day, U.S. and coalition partners targeted an ISIS unit near Baiji. Anonymous Iraqi Police sources claimed that airstrikes on that day destroyed 37 vehicles that were headed to clash with the ISF. If true, the report would either indicate that coalition and Iraqi Aviation were coordinating strikes in support of ISF movement, or that the coalition was able to target a particularly large gathering of forces.

By the end of October 30, Iraqi Army reinforcement had arrived at the outskirts of Baiji, positioning tanks at city entrances to shell ISIS positions within the city. Local sources reported that 150 Baiji youth had joined the security forces by that day as well.

In response, ISIS took defensive measures on October 30. ISIS detonated a Suicide Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device (SVBIED) targeting a security patrol on the road from Mazraa to Baiji. In an attempt to subdue Baiji’s tribal population, ISIS fighters used IEDs to destroy the home of Ghalib Nafous al-Hamad, a sheikh of the Jisat tribe, in central Baiji. ISIS also reportedly executed 17 other members of the Jisat tribe.

Despite these efforts, on October 31 a joint ISF and Shi’a militia force launched an assault on Baiji proper, making gains in the western, southern, and eastern parts of the city. On the same day, Baiji’s Iraqi Police opened a new office in al-Hajjaj, rallying security forces that had previously reported to the police office inside the city. The IP called for Baiji policemen and tribal elements to hold the territory south of Baiji so that security forces could advance further. Over the course of October 30 and 31, U.S. and coalition partners targeted an ISIS unit near Baiji, and a large ISIS unit north of Tikrit. By November 1, ISF had reportedly seized the main road in the city. Reinforcements began to clear Baiji and the Seneya area to the north, starting to dismantle IEDs on the road leading to the Baiji Oil Refinery.

In response, on November 4, ISIS began a campaign of mass arrests in Baiji, forcing youth to fight alongside ISIS, and to act as human shields for ISIS fighters moving heavy weapons from the city’s center to its outskirts. Dozens of families reportedly fled from Baiji and Seneya, towards the Abbas and Zab sub-districts of Hawija. On November 5, ISIS further encouraged this flight by detonating IEDs in 20 houses belonging to tribal sheikhs and ISF personnel in Baiji. ISIS also executed seven members of the same family in the Shawish district of Baiji on November 6.

As of November 12, ISIS retains a presence in the city, but has not been able to mount a successful counterattack. The ISF repelled an ISIS attack on Mazraa on November 1, and another attack on the Baiji Oil Refinery on November 3. U.S. and coalition forces conducted airstrikes against ISIS positions outside of the city on November 3, while IA Aviation bombed ISIS positions within the city on November 4. The air campaign continued on November 6, with IA artillery and IA Aviation shelling ISIS positions. ISF also attacked ISIS on the ground, making gains in the al-Buayji sub-district of Baiji on November 6, and destroying ISIS SVBIEDs on November 7.

In the next few days, between November 7 and 10, U.S. and coalition partners conducted 7 airstrikes near Baiji. Also on November 10, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) used Reaper remotely piloted air systems (RPAS) north of Baiji to target ISIS members planting IEDs. By November 10, ISF had captured the police directorate within Baiji, and were stationed 3 kilometers from the Baiji refinery. On November 11 the ISF cleared central Baiji, taking control of the Fatah mosque and the municipality building, where Baiji mayor Mahmoud al-Juburi reportedly resumed his duties.

Some ISIS elements remain in the city, as demonstrated by an ISIS suicide attack on November 11. Coalition airstrikes are ongoing near Baiji, with 5 strikes reported between November 10 and 12. Yet there are signs that ISIS is retreating: on November 12, an anonymous security source in Salah ad-Din reported that ISIS forces “almost completely” withdrew from Baiji using the Fatah bridge, likely heading southeast to Alam.

In response to the ISF offensive, ISIS’s defensive objectives are to prevent ISF from gaining freedom of movement on Mosul-Tikrit road, and to ensure adequate redundancy in ISIS interior lines used to move fighters and resources between Mosul and Anbar. ISIS’s offensive objectives are to continue its Anbar and Baghdad efforts, but now with a newly urgent need to disperse the ISF so that they do not mass at a point of ISIS weakness.

In the days following ISF movement into Baiji city, ISIS undertook defensive measures south and southeast of Baiji to prevent further ISF encroachment into ISIS areas of control. These ISIS attacks were directed both at security forces directly on the Baiji-Tikrit highway, and at local and tribal leaders in nearby urban areas, particularly in ISIS-held Tikrit and Alam. On November 1, ISIS forces, including suicide bombers, attacked ISF positions at Tikrit University, north of Tikrit. The next day, on November 2, ISIS detonated explosives inside of 7 homes in Alam, including the houses of the chairman of the regional sheikh council, the chairman of the regional security committee, and a regional TV channel director. ISIS detonated another bomb inside a house south of Tikrit on November 3, during the course of ISF and Popular Mobilization (units that include Shi’a militias) operations in the area. On November 5, ISIS further emplaced IEDs on the homes of 50 ISF personnel in the Qadisiyah neighborhood, north of Tikrit. This was followed on November 7 by a “massive” SVBIED attack launched against IA and Popular Mobilization units in Awja, south of Tikrit. Attacks on security patrols, offensive IEDs, and an escalation in the significance of targets are all signature signs of ISIS disruption, recalling al-Qaeda in Iraq’s (AQI) historic response to pressure from U.S. forces in 2007 and 2008.

In this current period of urban control, ISIS disruption is also evident from widespread retaliatory attacks against civilian residents of occupied areas. Two days after the ISF began its assault on Baiji proper, on November 2, unidentified gunmen reportedly distributed leaflets in Alam, near a square where the ISIS flag was reportedly burned and replaced with the Iraqi flag. The group claimed responsibility for the flag burning and the killing of ISIS members, and also called for residents to fight ISIS. ISIS responded harshly, destroying homes as described above and arresting 70 individuals, mostly of the Jubur tribe.

ISIS’s need to secure Alam was made more urgent by ISF pressure from the west at Baiji and Tikrit, and from the east at Tuz Khurmatu and Suleiman Beg. On November 9, ISIS used loudspeakers in Alam to warn members of the Jubur tribe that they had four hours to vacate the area or be killed. The next day, on November 10, mortar rounds reportedly landed on an ISIS gathering in Alam. ISIS consequently arrested 3 individuals in the area. On November 11, ISIS deployed 15 SUVs loaded with weapons to the area.

It is likely that ISIS forces that withdrew from Baiji on November 12 redirected southeast in order to secure Alam. Anonymous security sources reported that after withdrawing from Baiji ISIS deployed 400 fighters in 100 cars throughout Alam on November 12, placing VBIEDs and members wearing SVESTs in agricultural areas in the city. ISIS also abducted 50 individuals from the Jumaila village in Alam, and detonated IEDs to demolish the house of a cleric known for his anti-ISIS stance, Abu Manar al-Alami. As a result of ISIS operations, 80% of Alam residents have reportedly fled towards Kirkuk, Balad, and Samarra.

ISIS’ defensive operations have possibly also extended northeast of Baiji. On October 30, as ISF forces approached Baiji proper, ISIS forces detonated explosives on the railroad tracks running alongside the Fathah Bridge, which connects Baiji to Hawija. ISIS also emplaced IEDs on the bridge, ensuring the ability to destroy the bridge if needed to impede ISF movement. The next bridge crossing the Tigris to the north is near Mount Makhoul, where on November 10 the Iraqi Ministry of Defense announced that Iraqi fighter jets killed 40 ISIS militants. ISIS appears to be expecting an ISF advance into southwest Kirkuk. On November 11, an anonymous security source reported that ISIS initiated a conscription program in Hawija district and Riyadh, Zab, Abbasi, and Sharrad sub-districts, ordering each household to nominate a young man who would fight when ISF forces reached the area.

Offensively, ISIS will likely continue its Anbar efforts, with a strengthened requirement to disperse ISF manpower, and to close gaps between its areas of control in the region. ISF forces have been in a weakened position in Anbar, while ISIS’s proximity to Baghdad from the west and increased killing of Iraqi tribesmen has attracted the ISF’s attention. With a recent defeat at Jurf al-Sakhar, a likely withdrawal from Baiji, and a stalled offensive at Ayn al-Arab/Kobane in Syria, ISIS will likely its direct efforts towards Anbar.

It would be reasonable to expect ISIS to undertake renewed offensives at Haditha or Amiriyat al-Fallujah, current gaps in ISIS’s Anbar line of control. However, ISIS will have to weigh its gap-closing objectives with ongoing ISF counteroffensives, especially around ISIS-controlled Hit. This concern is heightened by the increased involvement of U.S. forces in Anbar, namely the arrival of 50 U.S. Marines at Asad Air Base, west of Hit, to train 400 tribal fighters.

In order to politically divert the ISF, ISIS will likely continue, and possibly ramp up, its efforts to stoke sectarian tensions. Mass executions of the Sunni Albu Nimr tribe are ongoing in Anbar. This targeting of tribal Sunni populations has been paired with a series of VBIEDs and SVBIEDs in Baghdad, most targeting Shia ‘Ashura gatherings and security checkpoints. Between November 1-3, 3 SVBIEDs and 3 VBIEDs detonated across Baghdad. On November 4, ISIS also detonated an IED in Latafiyah, southwest of Baghdad, targeting civilians returning from an Ashura pilgrimage to Karbala. While these explosive attacks in Baghdad are to be expected, especially during Shi’a holy days, it is prudent to watch for additional signs of ISIS attempting to divert tribal and Shi’a militia support away from a Za’ab-centric effort.

If the ISF gains control over the Baiji-Haditha road, then ISIS will likely give renewed attention to the Syrian supply corridor through northwestern Iraq. The stretch of the Jazeera desert from Raqqa to Mosul is vital connective tissue between ISIS political centers of gravity. Without access to the Samarra-Ramadi or Baiji-Haditha roads, the territory may also become a necessary supply route between northern Iraq and the Euphrates corridor. ISIS will likely pressure Kurdish forces in northwestern Iraq to ensure freedom of movement in this corridor.

Control of Baiji would provide the ISF with the unprecedented opportunity weaken ISIS at a place of core military strength. A strategy to inflict the most damage to ISIS should set conditions for a maneuver assault on Mosul. This involves both pushing north to Hawija, Qayarah, and Sharqat, and also swinging west to Tal Afar. When Iraqi Security Forces begin operations to clear Mosul in the spring of 2015, they will thus be positioned to approach from the west and the south, isolating the city from possible avenues of ISIS reinforcement.

The ISF should exploit Baiji’s position as a central point in ISIS’s Iraq theater. Denying ISIS access to routes in central Iraq would cut the connection between ISIS forces in Anbar and the Za’ab, and would isolate ISIS forces between Tikrit and Samarra. Severing these links between forces would limit ISIS’s ability to coordinate efforts across fronts. Consolidating control in Baiji and the surrounding routes and moving outwards would set conditions for an eventual ISF offensive on Mosul.